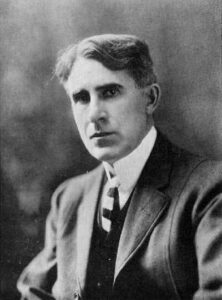

Pearl Zane Grey (1872–1939) was an American author best known for his popular western adventure novels and stories. Riders of the Purple Sage (1912) was his best-selling book, and his westerns are still widely read, with many never having been out-of-print. In addition to the perennial commercial success of his individual books, a monthly subscription book club, over 100 film adaptations, several western television series episodes and a television series, Dick Powell’s Zane Grey Theater, have been based on Grey’s novels and short stories.

Pearl Zane Grey (1872–1939) was an American author best known for his popular western adventure novels and stories. Riders of the Purple Sage (1912) was his best-selling book, and his westerns are still widely read, with many never having been out-of-print. In addition to the perennial commercial success of his individual books, a monthly subscription book club, over 100 film adaptations, several western television series episodes and a television series, Dick Powell’s Zane Grey Theater, have been based on Grey’s novels and short stories.

The fourth of five children, Grey was born and raised in Zanesville, founded by his great grandfather and one of the earliest settlements in what is now Ohio. It has been suggested that his name may have been based on newspaper accounts describing Queen Victoria’s mourning dress as “pearl gray.” His family had changed the spelling of their name to “Grey” after his birth, and by the time he attended the University of Pennsylvania on a baseball scholarship he had begun using “Zane” as his first name. Small, but tough and wiry, as a youngster Grey was an indifferent student and frequently in trouble over brawling and other roughneck behavior. In 1899 an ill-advised investment left the family financially devastated and his father, a dentist, moved them to Columbus, Ohio for a new start. An avid reader and accomplished fisherman, Grey roamed the rural countryside fishing and making house calls for minor dental procedures, having been trained by his father, until the authorities took note of his unlicensed dental practice and intervened. He also worked as an usher in a theater and played semi-pro baseball, resulting in scholarship offers from several colleges.

While at the University of Pennsylvania he played varsity baseball, studied dentistry, and began writing. During one summer break, while playing baseball back in Ohio, his father quietly paid a settlement to resolve a paternity suit brought against him. He graduated in 1896, having barely managed a passing average, and was torn between baseball and writing as a career, finally settling, unenthusiasically, on dentistry as the practical choice. He continued to play minor league and semi-pro baseball for several years while establishing a dental practice in New York as Dr. Zane Grey. His brother Romer, with whom he remained close throughout his life, played minor league ball professionally for several years and appeared in a single major league game for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1903.

While canoeing and fishing on the upper Delaware River in Pennsylvania with Romer in 1900 Grey met Lina “Dolly” Roth. Following a stormy courtship, during which Grey continued to see other girlfriends, the couple married in 1905 despite Grey’s warning that he had no intention of ever giving up his “freedom” or his “interest in women.” Throughout their marriage Grey had numerous mistresses and casual affairs, which Dolly seems to have viewed as a disability or weakness, rather than a deliberate choice. Dolly was highly intelligent and educated as a teacher, and after their marriage gave up teaching to assist Grey in his writing and manage the family, home, and Grey’s career. Grey’s early submissions were rejected for poor grammar and weak construction, and Dolly proved to be an excellent proofreader and editor, helping Grey to improve his writing.

Following several rejections, his first magazine story, a human-interest story about a fishing trip, was published in 1902. Grey happily distributed reprints in his dental office waiting room, but success came slowly. Inspired by Owen Wister’s The Virginian (1902), the first true western novel, Grey decided to write a full-length book. Betty Zane (1903), dealing with the Revolutionary War and frontier exploits of his family, was published at his own expense after being rejected by Harper & Brothers, probably with money provided by Dolly or Romer’s wealthy girlfriend. Two more books, Spirit of the Border and The Last Trail, were published in 1906 by A.L. Burt, both dealing with the frontier experience and based on his family history. Today these three books are sometimes collectively referred to as the “Frontier Trilogy,” but they met with indifferent success when published. The Last of the Plainsmen (1908) was written after Grey attended a lecture in New York in 1907 by Charles Jesse “Buffalo” Jones, a western hunter and guide whom Grey then befriended. Again, the book was rejected by Harper & Brothers before being published by “Outing” magazine.

After their marriage, Grey abandoned his dental practice to write full-time, made possible by an inheritance received by his wife. Dolly’s assistance was instrumental in improving the quality of Grey’s work, and as his career got underway she proved to have an aptitude for business and handled all negotiations with publishers and filmmakers while managing his literary career as well as their home and family. Following The Last of the Plainsmen, he wrote a series of juvenile novels and magazine articles. Grey’s breakthrough came with the publication of The Heritage of the Desert (1910), his first western and a best-seller, by Harper & Brothers. Written in just four months in 1910, it was typical of Grey’s writing style. Suffering from bouts of depression and mood swings throughout his life, Grey rarely wrote steadily, but rather wrote in furious bursts, sometimes producing 100,000 words in a period as short as a month, followed by dry spells lasting weeks or months and filled with travel, fishing, or inactivity.

In 1912 Grey published Riders of the Purple Sage, his most famous novel and one of the best-selling westerns of all time. Ironically, the editor at Harper who had criticized Grey’s early attempts repeatedly and finally accepted The Heritage of the Desert rejected Riders, but Grey took the manuscript to the publisher’s vice-president, who enthusiastically accepted it. This commenced a publishing relationship which would actually outlive the author, with Harper accepting manuscripts from Grey far faster than the publishing schedule allowed, leaving Harper with a stockpile of completed Zane Grey novels that they continued to publish at regular intervals after his death.

Within a few years, Grey’s series of successful novels had brought financial security that freed him to travel and engage his first and greatest passion: fishing. From 1918 to 1932 he used his position as a regular celebrity contributor to “Outdoor Life” to introduce big-game fishing to the American public while traveling several times to Florida for deep-sea fishing excursions of his own. He was also a frequent visitor to the fishing camps of Nova Scotia. From 1923 to 1930 he spent several weeks each year at his cabin in central Arizona. He also kept a cabin on the Rogue River in Oregon and traveled in Washington state and Wyoming. Beginning around the mid-1920’s and through the 1930’s Grey traveled farther and for longer periods, leaving his family behind. In 1926 he visited New Zealand for the first time, returning for four months in 1927, a like stay in 1928-1929 and three months in 1932-33. Grey wrote about these experiences, making the Bay of Islands area a popular destination for the rich. From 1928 on he frequently visited and fished the waters of Tahiti, and in the 1930’s he helped establish and popularize deep-sea fishing in Australia. Grey held various world records at times for the size of different varieties of fish he caught, and is credited with the invention of the “teaser,” a type of bait still in use today to attract fish.

While the Great Depression hurt the publishing industry generally and sales of his works and magazine serializations slowed, he continued to receive substantial royalties from earlier works and increasingly gained a new source of income from films. Grey had sold the original film rights to Riders of the Purple Sage in 1916 for $2,500, approximately equal to $56,500 today. In 1918 Grey moved his family to California, in part to be nearer the film industry. Other film adaptations followed, and the growth of the film industry the 1930’s would see approximately fifty film adaptations of Grey’s westerns. He formed his own production company, which he sold, after producing seven pictures based on his own books, to a partner of the founder of Paramount Studios, which quickly absorbed Grey’s company and employed Grey as an advisor. Many of the earliest westerns filmed on location were based on Grey’s stories, in part because Zane Grey was by then a household name and projects associated with his popular works were considered “bankable.”

Professional critics and literary “experts” found little to like in Grey’s work, most finding that it “lacked substance,” displayed a “skewed” sense of the “morality” of the west, and was too violent and too fanciful. Other criticisms were that Grey lacked style, or that his work was “stiff” or “unpolished.” The reading public obviously disagreed. Grey published over 90 books, including those published posthumously and originally published as magazine serials, which have sold over 40 million copies. Grey placed nine different books on the top ten bestsellers list between 1917 and 1926, with sales in excess of 100,000 copies each time. One of the first millionaire authors, sales of Grey’s books exploded all over again in the 1940’s and 1950’s with the advent of paperbacks, and more of his books have become films than any other author.

Grey died of heart failure on October 23, 1939, but new Zane Grey westerns continued to appear until 1963, when the backlog of manuscripts was finally exhausted. Like Owen Wister with The Virginian, Zane Grey was able to make “the west” a part of his characters and stories, not merely a “background.” They are not novels set in the old west, they are true “western” novels. With the success of Grey’s works at Harper & Brothers the western became the dominant genre in popular fiction, supporting multiple western-themed pulp magazines. Grey’s works became the standard based upon which other publishers sought to get into the “western” market, and with writers like Max Brand, Ernest Haycox and, later, Louis L’Amour following in Zane Grey’s footsteps, Grey became one of the foremost influences in building the image, and mythology, of the American West.

Commentary (c) Owen R. Howell, Used by permission.